The 6th Century BCE was a remarkable period in the history of the Indian subcontinent. It witnessed the rise of the Mahajanapadas, the first-ever political states and cities on the Subcontinent. This, alongside a commodity surplus and the flourishing of trade, society, and art, paved the way for a complex economy. This then demanded a monetary system with a uniform, stable currency, and a robust authority to assign assurance marks on the coinage. The result was a piece of metal of sufficient purity and weight certified by the ruler of the territory. There’s a good chance these punch-marked coins were originally struck through guilds or private merchants, and later went under royal control. Hoards of silver punch-marked have been unearthed in a range of locations in northern India, from the Taxila-Gandhara region of northwestern India to the middle Gangetic valley and in southern India.

Decoding symbols

In 1890, British naturalist W Theobald of the Geological Survey of India started examining the symbols on silver punch-marked and noticed they represented a range of forms, including hills, mammals, reptiles, humans and various objects. Based on his deductions, two numismatists DR Bhandarkar and DB Spooner made the case that the punching of a range of symbols followed a particular pattern and that these had been the royal issues. Their study paved the way for scholars to further examine punch-marked coins for details like material, mass, geographic area, period of circulation, measurements, etc.

This is not to say that all punch-marked coins can be assigned to a particular king or dynasty. The origin of symbols on these coins can also be traced back to prehistoric subcultures that conveyed information via symbols and drawings.

As previously mentioned, these coins bore no inscriptions, only geometric designs and figures from nature, like the sun, moon, mountains, animals, plants, etc. Some also covered human figures. Today, the inscriptions on these coins are no longer clear or even legible in some cases so it’s hard to comment on their importance. But it is likely these symbols were of political or religious significance.

These coins had been at first stamped with marks only on one side, the other facet being blank. Researchers later observed Shroff/guild marks on them. Since the symbols indicate no particular ruler or period, it is very tough to confirm who made them or when. But each symbol is limited to either coins of a particular place or those of a specific variety. This helps differentiate the coins of one country from that of another.

Thinking local

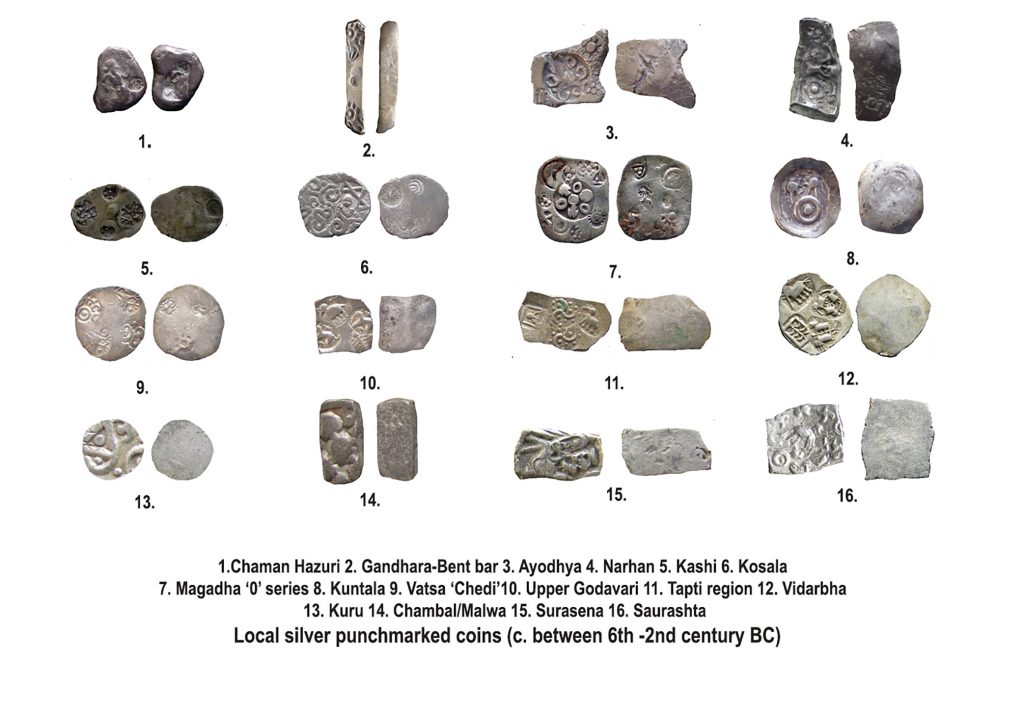

On the basis of the symbols, punch-marked coins may also be divided into two large groups, the local or Janapada series and the imperial or universal series. Early punch-marked coins typically carry one to four symbols. While the symbols varied by type, conis were characterised by specific weights. These coins are from a period when India had many janapadas (small states) and few mahajanapadas (large states). Presence of the Buddhist text “Anguttar Nikaya” would suggests the coin hailed from one of the 16 mahajanapadas: Anga, Ashmaka, Avanti, Chedi, Gandhara, Kashi, Kamboj, Kaushal, Kuru, Magadh, Malla, Matsya, Panchal, Surasena, Vajji, and Vatsa (see map). A coin with four symbols likely originated from Kashi, Magadha, Kosala, Chedi, Avanti, Dakshina Kosala or Ashmaka. And those with single symbols were used in Surasena (Mathura), Saurashtra (Kathiawad), Malla (Kushinagar and Deoria) and Kuntala (Satara).

Here’s a handy guide to identifying the origins of silver punch-marked coins:

- Gandhara issued some atypical coins in the shape of lengthy concave bars, with symbols punched on both ends. The coins of each of these janapadas vary on the basis of material, weight, metal quality and symbols.

- While in all other states, coins were made by stamping pieces cut from a metal sheet, in Kuntala, a pulley system was used to punch recently poured molten metal while it was still soft.

- The symbols found on coins from the Kosala janapada were usually geometrical patterns representing a bull, elephant or hare. Composed of three S-like curved lines around a circle, the Kosala stamp is easy to recognise.

- Surasena coins have a cat or a lion-like animal atop a hill, or symbols of taurine, triskeles, crescent, etc. The reverse usually remained almost blank.

- The symbol of hills, a tree within railing, Goddess Lakshmi, an elephant and a bull were all commonly depicted on Saurashtra coins.

Going universal

Between the mid-6th and 4th century BCE, these janapadas and mahajanapadas had been steadily consolidated into the Magadha empire, which covered most of the Indian subcontinent and whose coins are now found all over the country. These are termed the imperial or universal series.

Due to the spread of Buddhism and the vast network of maritime trade, silver punch-marked coins circulated beyond their territory, going to the Chera, Chola, and Pandya kingdoms of south India, and onwards to Sri Lanka.

The coins in this category are grouped by series and the imperial coins were placed in the eighth series, which dates from the onset of Magadha as a janapada up to the time of the Mauryan empire. The symbol of the sun is present in nearly all groups. A second symbol of a complex six-armed figure puts various varieties in the same group. A third symbol in the classification consists of coins with strong affinities, having hill, taurine and other motifs. The fourth series is assigned to symbols inside the above class. The fifth varies generally and showcases a hide-and-seek pattern—coins in this series are found in the greatest numbers. There are over 625 symbols used in a variety of combinations on punch-marked coins.

The coins may also be assigned a series range primarily based on the fabric. Series one and two take skinny fabrics. Medium fabrics are seen in the second and third series. Series four and five are occupied by each medium and thick fabrics. Series six and seven are of thick material. The primary four sequences have either minute opposite punch-marks or are left blank. Series five usually has bold punch-marks. Series six and seven have bold punch-marks on the reverse.

Different coins for different kings

Besides the Mauryans, coins using the same technique were issued in the Pandya territory too. Though half the weight of the Mauryan punch-marked coin, these still included the sun and six-armed symbols. However, the Pandya dynasty introduced three new symbols of their own. On the reverse was typically seen a fish symbol, harking to the Madurai area. Like the Pandya territory, the vicinity of Vidarbha (in Maharashtra) too was marked by distinctive patterns for punch-marked coins. Punch-marked copper coins categorised under the seventh series through the Gupta and Hardaker empires and that belong to the post-Mauryan period have been found in Patna, Bhagalpur, Mathura, and parts of central-western India.

According to the Arthashastra, silver coins issued from Mauryan mints came in four denominations: pana, ardha-pana (half pana), pada (quarter pana) and asht bhaga (one-eighth of a pana). So far, coins found hailing from the Maurya era weigh 50-52 grains (3.23-3.37gm), however, some of these have been found cut in half and these also seem to have been in use. Some minute coins weighing between 2 and 3 grains (0.13 to 0.19 gm) made by flattening metal globules and stamping them with a symbol have also been found alongside the panas.